Literacy Learning Disorder

As mentioned above, learning to read and write requires formal instruction, which is usually carried out in educational contexts at the early stages of schooling. In Western countries, where alphabetic orthographic systems predominate, letter learning begins between the ages of 3 and 5, depending on the educational system of each country.

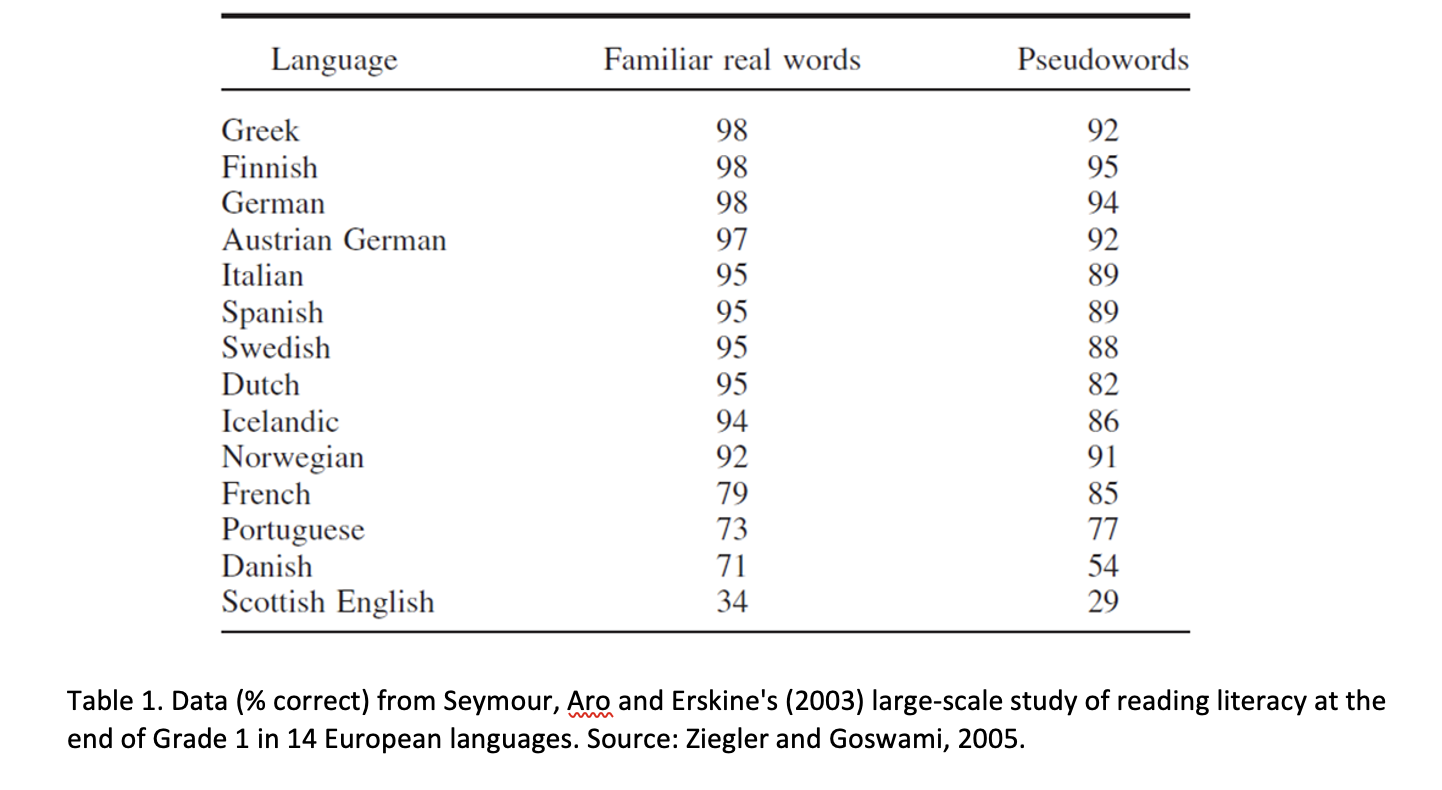

Generally, children are relatively fluent readers by the age of 7 or 8, although there are differences depending on the depth of the orthographic system. Thus, in transparent or superficial systems, such as Greek, German or Spanish, reading accuracy is achieved quickly and reading practice leads to a significant increase in speed in one or two more years. In contrast, in opaque or deep orthographic systems, such as English, it takes longer for children to achieve fluent and accurate reading (see below for a comparative table of hits on familiar and invented words in 5- and 6-year-olds belonging to different orthographic systems).

Although these differences are normal depending on the language, sometimes some children have more difficulties than their peers in achieving fluent reading, both in words and texts. These difficulties may be due to a variety of reasons, such as the child’s low intellectual level, neglect by parents or teachers, situations of exclusion or even the use of inappropriate teaching methods. However, some children present specific difficulties in learning to read and write despite the absence of all these possible explanatory factors.

This condition, called developmental dyslexia, is defined as a “specific learning difficulty, of neurobiological origin, characterized by difficulties in accuracy and/or fluency in word recognition, as well as deficits in writing and decoding skills. These difficulties result from a deficit in the phonological component of language, which is often unexpected in relation to other cognitive abilities and adequate school instruction.”

It is important to highlight two aspects of the above definition:

The first is the neurobiological origin. It refers to the fact that specific difficulties in learning to read and write usually have a hereditary component (the probability of a child having dyslexia is greater if one of his parents also has it) and also present certain anomalies in brain volume and activity (specifically, they usually show less grey matter volume and less activity in left temporo-occipital and temporo-occipital areas, while in the right frontal area, both grey matter volume and activity are increased).

The second important aspect of the definition is the deficit in the phonological component of language, which seems to be the cause of difficulties in learning to read and write. This implies that children with developmental dyslexia have difficulties in handling phonemes (discriminating, substituting…), which makes it difficult for them to learn and automate the rules of grapheme-phoneme conversion, as well as the formation of orthographic representations of words in their lexicon. This hypothesis is supported by the difficulties of phoneme management by dyslexic children, even when it comes to oral language. Thus, these children have difficulties in spelling words, looking for rhyming terms, repeating, especially when it comes to long pseudowords, and present phenomena of having it on the tip of the tongue more often than their peers, which is explained by difficulties in accessing the phonology of words. In short, children with dyslexia present problems of phonological awareness, which especially affect them in learning the alphabetic code and in the acquisition of fluent reading.

In the case of dyslexic children, differences are also observed according to the depth of the orthographic system. Thus, in transparent or shallow orthographic systems they will have difficulties, especially in speed; in terms of accuracy, although they also have difficulties, they will not be as striking as in opaque systems, since they must learn a few rules of grapheme-phoneme conversion. In opaque or deep systems, on the other hand, children with dyslexia will have difficulties in both accuracy and speed.

As far as writing in dyslexic children is concerned, a very high percentage presents problems, also due to difficulties in the handling of phonemes. These difficulties are also present in both ways: phonological, which hinders the learning and automation of phoneme-grapheme conversion rules, and lexical, which hinders the formation of orthographic representations of words in their lexicon. The result is slow writing and abundant errors of two main types:

- Phonologically plausible: those in which the sound of the word is not modified despite being misspelt. They indicate errors in the absence of orthographic representations for those words. E.g.: “cabayo” instead of “caballo”.

- Phonologically non-plausible: those in which the reading (pronunciation) of the word is modified. They indicate errors in the application of the phoneme-grapheme rules. E.g.: “raceta” instead of “racket”.

Difficulties in letter formation, although they may occur, are much less frequent.

GOOD PRACTICES:

- Children with dyslexia often have phonological awareness difficulties, so these types of tasks can be useful in detecting these problems even in children with a different native language. Some tasks can be:

· Detect phonemes in words presented orally (we can help us with drawings). E.g.: which of these words contains the sound “…”?

· Omitting phonemes in words presented orally. E.g., what would the word “” look like if we remove the sound “…”?

· Adding phonemes in words presented orally. E.g., how would the word “” sound if we add the phoneme “…” at the beginning/middle/end?

· Say words that rhyme with each other

· Repeat invented words, increasing the length progressively (e.g., play at making up words by adding one syllable at a time and trying to say the whole word each time: ca - cade - cadepo - cadepora - cadeporato…). - Children with dyslexia usually have a much higher performance in oral language than in reading and writing. Substantial differences in performance on tasks depending on their oral or written presentation may lead us to suspect the presence of specific reading and writing problems.