Opaque vs. transparent orthographic systems

Reading is a complex process which involves accessing a string of phonemes and/or meaning from a visual stimulus (graphemes). As explained above, there are different orthographic systems which differ in the unit which these graphemes represent. Thus, in logographic systems each symbol represents a complete word, in syllabic systems it represents a syllable and in alphabetic systems, each grapheme (i.e. letters or digraphs such as “ch”, “ll” or “rr”) represents a single phoneme of the language. This implies that people, in order to read, will have to learn more or less graphic symbols depending on their spelling system since in any language there are more words than syllables and more syllables than phonemes. This is known as the Granularity Problem.

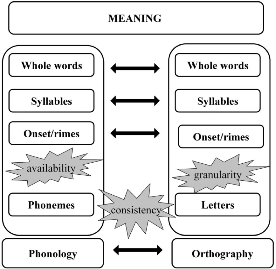

Figure 1. Problems in learning to read: availability, consistency and granularity. Source: Ziegler and Goswami, 2005.

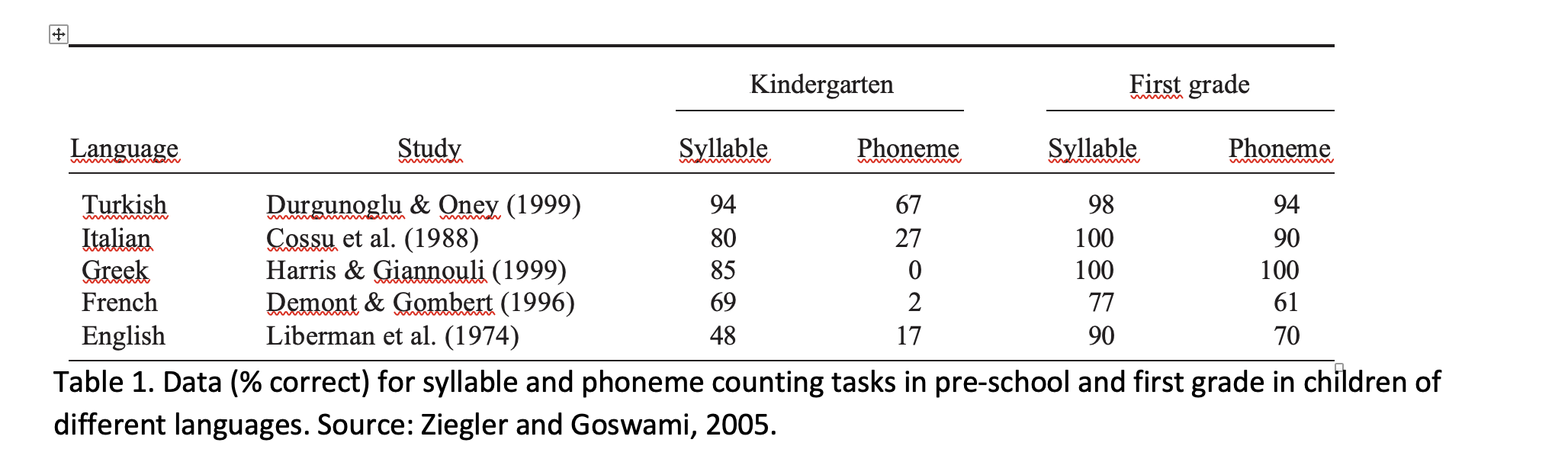

A second problem that affects only alphabetic systems is the Availability Problem. This refers to the fact that not all units of language are explicitly or consciously accessible during the learning of reading, and it is necessary to develop this knowledge in order to achieve effective literacy learning. Those units that are not explicitly accessible are phonemes. Studies show that pre-reader children and illiterate adults can understand the concept of syllables, but not the concept of phonemes (see Table 1).

The concept of a phoneme is acquired through reading and is necessary for the correct learning of both reading and writing since in alphabetic orthographic systems each grapheme corresponds to a single phoneme.

This brings us to the third and final problem, which is the Consistency Problem. It has to do with the fact that some orthographic units have multiple pronunciations (e.g. in English, the “a” in “saw”, “cat” and “made” sounds different) and, conversely, some phonemes can be written in different ways (e.g. in Spanish the sound /b/ has two spellings: “b” and “v”). The presence of inconsistencies in grapheme ↔ phoneme correspondences slows down the learning of literacy, but it is important to bear in mind that different languages differ in the consistency of their orthographic systems, leading to great variability in the speed at which children learn literacy.

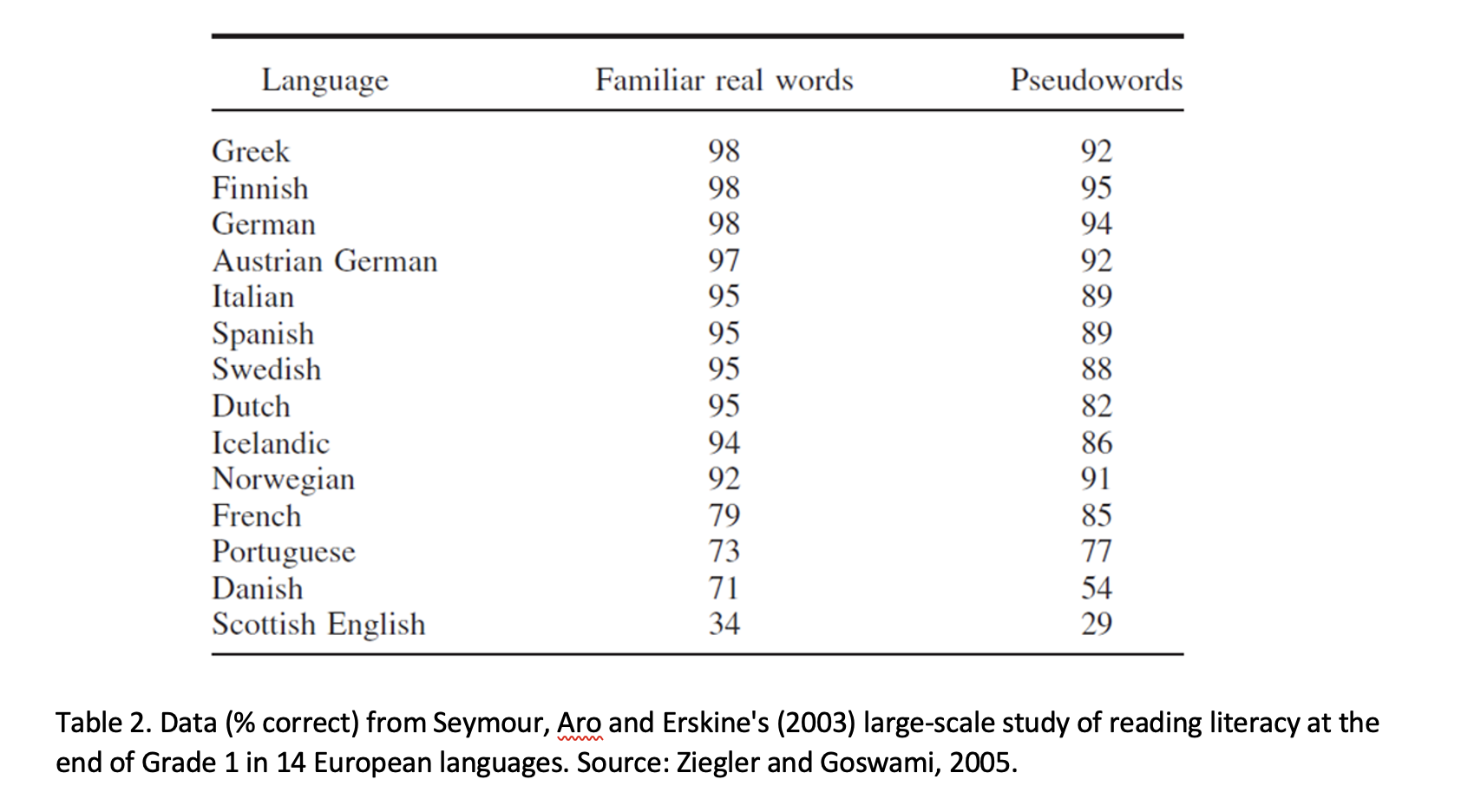

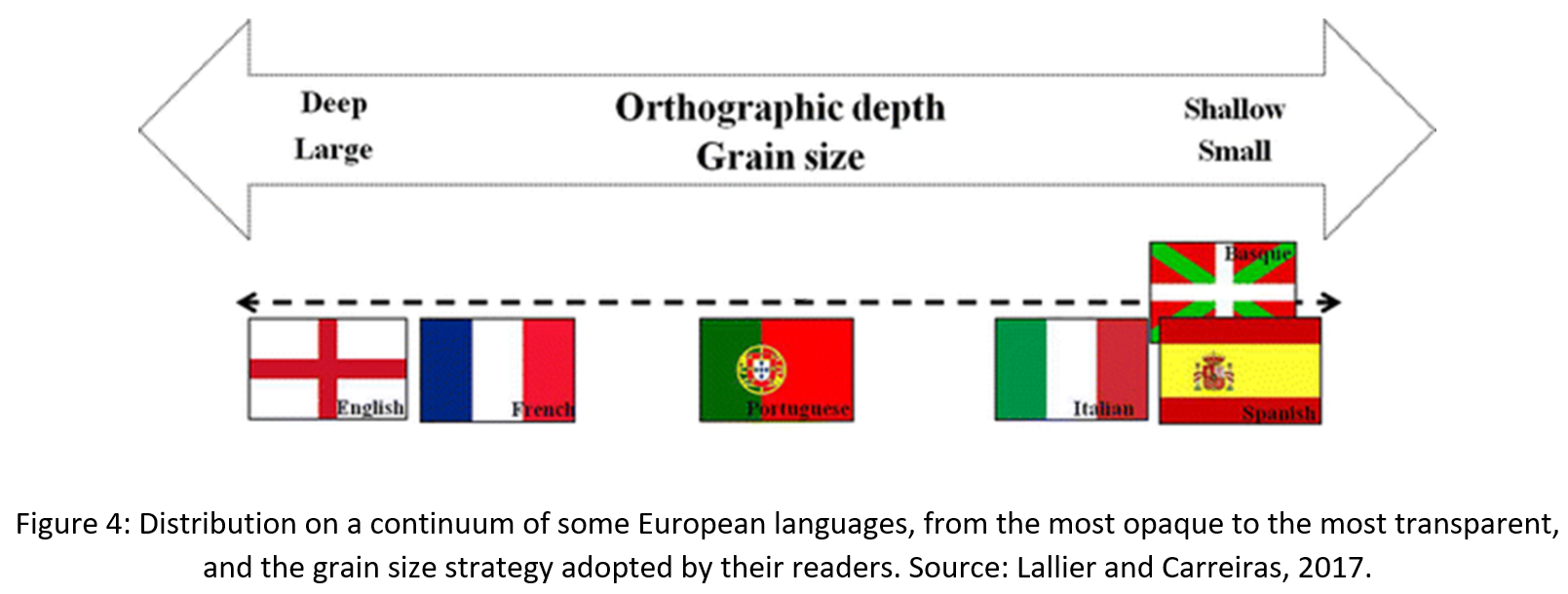

All languages lie on a continuum of opacity-transparency, with transparent languages showing high degrees of consistency in grapheme-phoneme correspondences. In transparent languages, learning to read is faster, as the child has to learn only a few grapheme-phoneme correspondences. In opaque languages, on the other hand, the same grapheme may have different pronunciations due to the existence of irregularly read words, which are exceptions to the general rule, and in these orthographic systems, children take time to achieve accurate and fluent reading (see Table 2 for comparison between languages).

The simplicity of syllabic structure and a limited repertoire of vowel phonemes in the language further facilitate the learning of reading. Thus, for example, Table 1 shows how languages with simpler syllabic structures and more limited vowel systems (Turkish, Italian and Greek) show greater syllabic awareness from the earliest stages than other languages such as French or English, with more complex syllabic structures and more extensive vowel systems. Note that these differences persist even in the first grade of basic education.

Psycolinguistic grain-sized theory (Ziegler y Goswami, 2005)

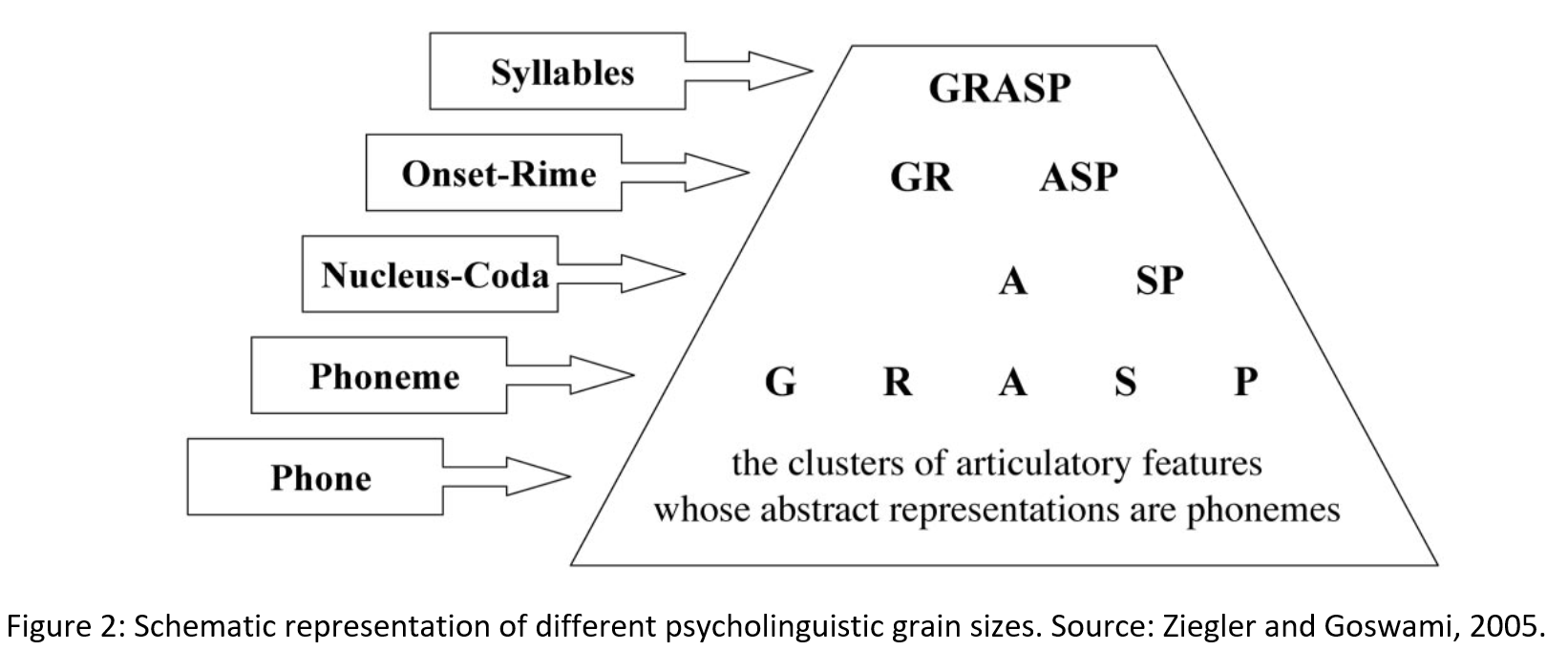

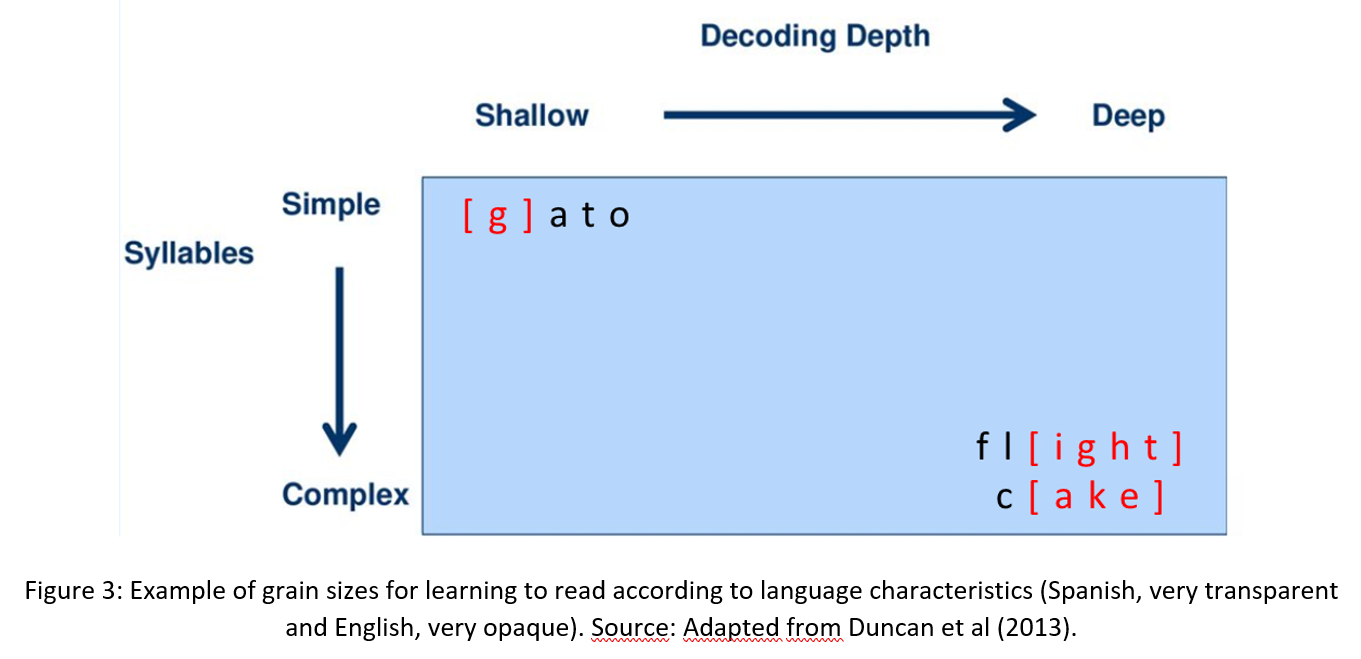

Taking all of the above into account, Ziegler and Goswami (2005) propose a theory according to which strategies for learning to read should vary according to the characteristics of the language. Thus, in very transparent languages, with high consistency in grapheme-phoneme correspondences, simple syllabic structures and limited vowel repertoires, the most appropriate strategy would be the small grain (i.e. the grapheme). However, in more opaque languages, with more irregular grapheme-phoneme correspondences, complex syllabic structures and large vowel repertoires, the most effective strategy would be the large grain, i.e. taking larger segments and teaching their correspondence at the phonetic level (e.g., syllables: “ture”: as in “creature”, “moisture”, “furniture”; rhymes: “ould” as in “would”, “should”, “could”; clusters: “aw” as in “awful”, “awesome”, “straw”; words such as “muscle” or “honour”).

In this way, and without excluding the teaching of grapheme-phoneme correspondences, children in each language should be trained to adopt the most appropriate strategies according to the characteristics of their orthographic system. The systematic teaching of these regularities could benefit the rapid and efficient learning of reading and writing.

GOOD PRACTICES:

- Reflect in groups on the spelling system of the dominant language in the class: is it transparent or opaque? Why? Give examples of words which do not conform to the rules of grapheme-phoneme or phoneme-grapheme conversion.

- Think also about the syllabic structure of the orthographic system of the dominant language: in general, are they complex syllables, i.e. made up of many letters? What is the longest syllable you can think of?

- Repeat these same activities with the orthographic (alphabetic) spelling system of the other languages spoken in class.